Why Canada Can Bridge the EU and CPTPP Trading Blocs

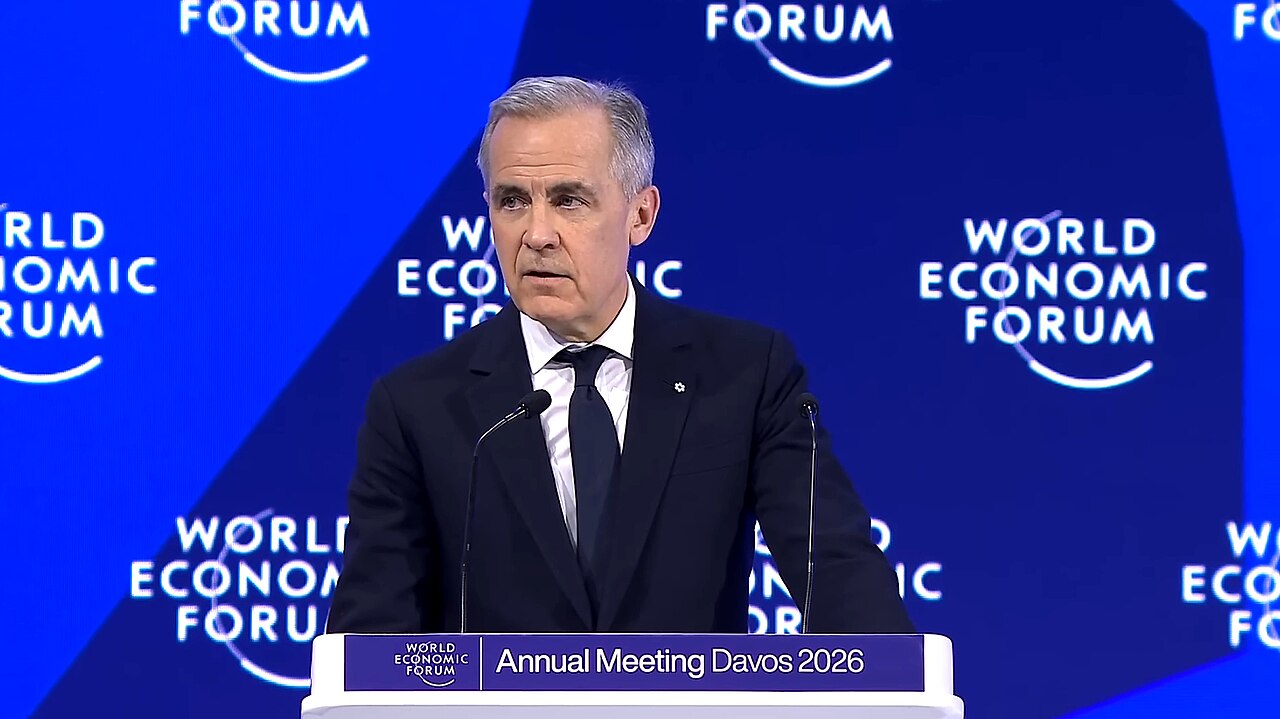

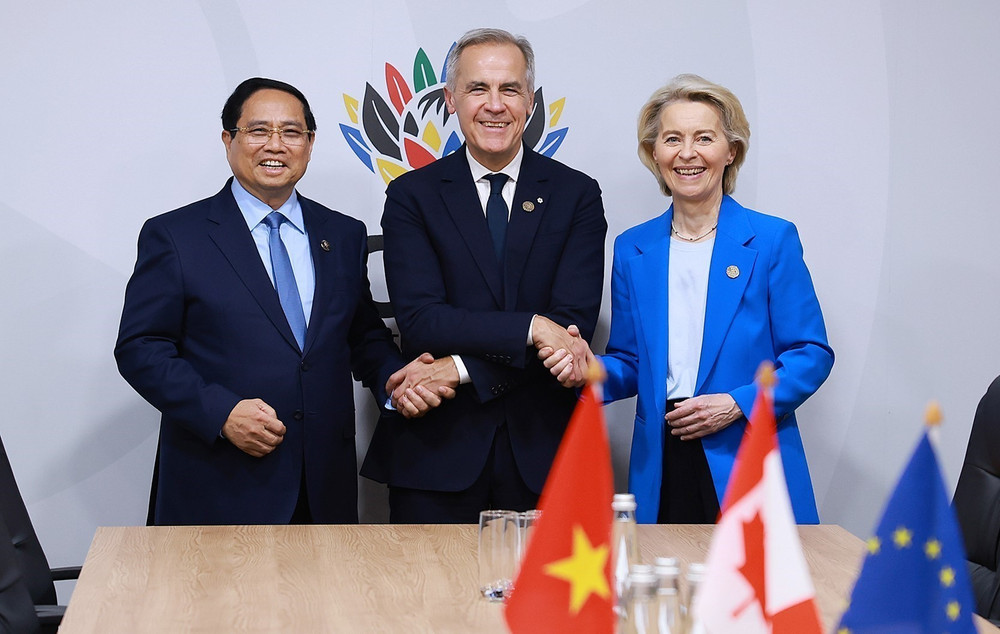

Prime Minister Mark Carney’s trip to India, Australia, and Japan comes at a critical time when Canada is racing to diversify its trading relationships while United States President Donald Trump slaps new tariffs on countries around the world. This week, Trump announced the 15-per-cent tariffs after the U.S. Supreme Court struck down his previous tariffs. Canada must explore every avenue to find new economic and trade partners, and Carney’s trip is a good sign that the government is pushing forward to make deals with countries that share our values as well as with countries that share our